I think I speak for many when I say that for “boomers” like myself—those

of us who grew up in the Cold War years of the post-World War II era—it is

singularly disturbing to witness how quickly the world appears capable of regressing

from the time of relative peace and cooperation painstakingly forged after the

fall of the Berlin Wall at the end of the 1980s to a frightening and paranoid climate

of East-West power struggles and the general panic that they engender. And just

let me say to those who aren’t

panicked and afraid, you probably should

be.

I think I speak for many when I say that for “boomers” like myself—those

of us who grew up in the Cold War years of the post-World War II era—it is

singularly disturbing to witness how quickly the world appears capable of regressing

from the time of relative peace and cooperation painstakingly forged after the

fall of the Berlin Wall at the end of the 1980s to a frightening and paranoid climate

of East-West power struggles and the general panic that they engender. And just

let me say to those who aren’t

panicked and afraid, you probably should

be.  As I have stated a number of times in both essays and public

presentations, I believe that we are currently facing the most dangerous time

for world peace since the Cold War era. And the development of this new—yet

old—climate of impending world violence has come at an absolutely dizzying

rate, since the collapse of tolerably good relations between Russia and the

West over the Ukrainian crisis—underscored by superpower rivalry in Syria and

the Middle East—following Moscow’s annexation of Crimea in March of last year.

As I have stated a number of times in both essays and public

presentations, I believe that we are currently facing the most dangerous time

for world peace since the Cold War era. And the development of this new—yet

old—climate of impending world violence has come at an absolutely dizzying

rate, since the collapse of tolerably good relations between Russia and the

West over the Ukrainian crisis—underscored by superpower rivalry in Syria and

the Middle East—following Moscow’s annexation of Crimea in March of last year.

People of my generation grew up in the shadow of potential nuclear

holocaust. After the United States leveled two Japanese cities at the end of

World War II and vaporized significant portions of their populations, it became

clear that the doomsday bombs weren’t just a “boogie man” invented to scare

would-be aggressors into maintaining peace, but a very real and devastating war

threat, capable of wiping out entire peoples, and, indeed, the human race, if

it ever came to a showdown between any of the most powerful countries on earth.

And every time we saw Russia, the United States and China flexing their

military muscles and refusing to back down from their intransigent stances—the

Cuban Missile Crisis (13 days in October 1962, when the US and Russia went toe to

toe over Russian ballistic missiles deployed in pro-Russian Cuba) is a graphic

example—we would become acutely aware of just how vulnerable the world was to

the whims and diplomatic tantrums of superpower leaders.

That basic fear, which had people digging “fallout shelters” and

practicing drills for “what to do in case of a nuclear attack” was quelled

after the breakup of the Soviet Union a quarter-century ago and the advent of a

new period of cooperation, not only between Russia and the West, but also between

still-Communist China and the Western nations. Of course there were still

nuclear warheads sitting in their silos and on board nuclear submarines “just

in case”, but we tried to learn not to worry about that, or about possible

mistaken signals setting off a nuclear exchange and so too, the end of the

human experiment. But we trusted that the Cold War was over and that we were

living in a saner and safer world, where, yes, there were wars, but proxy wars

fought by third parties with lower-tech weapons provided by the most powerful nations

on earth, not any potential clash among superpowers, the thought of which, only

a short time ago, seemed almost ludicrous.

But just over the course of the past 20 months, the superpower war

threat that we “boomers” grew up with and that most of us thought had been

banished forever, has been rearing its ugly head once again. And on analyzing

it, I fear that it is a much more volatile threat than in our more naïve past.

Or perhaps it’s that these current times that appear so overblown with

information are actually the naïve times, times in which certain world leaders

are delusional enough to actually believe that a clash among superpowers could

end in anything but disaster, or that anyone could come out of such a conflict

as anything like “a winner”.

|

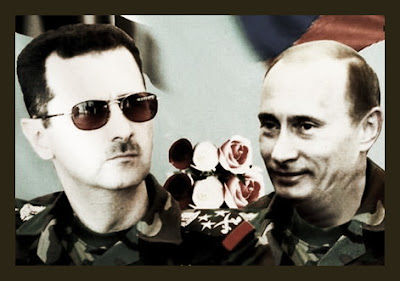

| Russian air raids in Syria |

Proof of this dangerous new trend has been in evidence for the last year

and a half or more. But it has become a whole lot more compelling over the past

few weeks and months. Russia’s October decision to take an active role in Syria

by running withering aerial and naval attacks on anyone opposing the

pro-Russian dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad. The refusal of both Russia and the

US to coordinate their air actions over Syrian territory, thus prompting a

situation in which the two countries’ pilots could end up facing off in Syrian

airspace. Russia’s disregard for the sanctity of Turkish airspace in carrying

out its attacks on Assad’s enemies, and the immediate response from not only

Turkey but also NATO, saying that violation of the airspace of a NATO country

is a violation against NATO as a whole and will not be tolerated. The decision

of the US, in the face of Russia’s new and decidedly more aggressive role, to

vastly increase its aid to Syrian nationalist irregulars fighting to overthrow

Assad. Moscow’s sudden and anxious courting of the government of Iraq, a US

ally since the fall of Saddam Hussein, in its fight against Islamic State terrorists.

China’s construction of islands that amount to permanent aircraft carriers and remote

military supply bases in the South China Sea and a provocative move by the

United States to use warships and warplanes to patrol those newly inaugurated islands

and to send an aggressive message to Beijing to stop building up its strategic

readiness. Similarly, China’s barely veiled threats of a military response if

the US doesn’t butt out of its affairs. Japan’s new signs of a desire to return

to being a military power after nearly three-quarters of a century of being a world

symbol and paragon of peace, following the horrendous lessons learned in

Nagasaki and Hiroshima. And NATO’s recent emergency meeting to take concrete

steps to prepare for new Russian imperialist designs—measures that include

doubling (from 20,000 troops to 40,000 troops) the Alliance’s rapid

intervention forces.

|

| US warships in the South China Sea |

All of these indicators are clues to the dangerous turn the international

climate is taking, a climate that is an eerie reminder of the state of

upheaval, distrust and lack of willingness to communicate and compromise in

which the world found itself precisely 100 years ago at the start of World War

I. But this is not the world of the

First World War. In today’s world the rules of engagement are no longer based

on honor but on winning at any cost. And the weapons of war today are

unconscionably more devastating, as witnessed in the crime scene photos—they

can be called nothing else—posted on the Internet of one of two Doctors Without

Borders hospitals “accidentally targeted” in airstrikes over the past week by

the US-led coalition in the Middle East and in which one saw paltry and only

partial skeletal remains of patients literally vaporized where they lay in

their beds during that airstrike.

|

| US fighters over the Middle East |

Dead civilians are no longer referred to, under the new rules of engagement,

as victims, but as “collateral damage.” Compelling statistical trends show that

in the great majority of wars since the Vietnam War era, between five and nine

out of every ten victims of contemporary conflicts are innocent civilians. That’s

a whole lot of “collateral damage”. And to my mind, that ratio today makes any

war whatsoever a war of aggression and, as such, a crime against humanity.

On a final note, let’s be clear about what the reckless behavior that

world leaders are currently displaying in drawing lines in the sand and daring

each other to cross them means to people like you and me. What it signifies is

that the human race as a whole is potentially in danger of becoming “collateral

damage” and until we start taking action to strip our leaders of the power to

involve us in war, we will continue to be accomplices in our own destruction

and hapless victims of our own apathy.

Comments

Post a Comment